London-based photographer Gabby Laurent makes elegant, spirited images that are the result of an encounter between performance and photography. ‘A lot of my work tends to use my own body to make it’, she says, ‘as a gestural form to symbolise something else.’ To make her self- portraits, Laurent is both in front of the camera and ‘behind’ it – she uses a hand-held button connected to the camera by a long cable, called a cable release, to capture images of her own body in motion.

"A lot of my work tends to use my own body to make it’, she says, ‘as a gestural form to symbolise something else."

In some of her photographs, Laurent appears graceful, like a dancer, elsewhere she seems more awkward, calling to mind the great comic actors of the early 20th century - Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton. What is true of all her work is that it explores the way that the body and mind are linked – how the way we move can reveal something about our psyche, our emotions or our relationships. This quality recalls the work of American artist Bruce Nauman, who was the subject of a recent retrospective at Tate Modern. Speaking of Nauman and other artists she particularly admires, Laurent says: ‘Nauman is someone I really resonate with, his humour and depth - I have this quote by him written in my notebook; 'art is a means of acquiring an investigative attitude'. I think that' such a privilege of making work. Also, Ana Mendieta, Helena Almeida, John Baldessari, Franz West and John Divola...A lot of performative photographic work from the 1960's and 1970's that I love. Artists who were not wanting to be confined to gallery walls, they were making work in the landscape or in their studios and using a camera to document it. There was something very unpretentious about this at the time. The photographs aren't always technically proficient, but it has an urgency and power that I think is so exciting.’

For a recent series, called Falling, Laurent photographed herself ‘just falling over in various places’, with both humorous and dramatic effect. She was interested in how, by intentionally falling over, she is forced to let go of control, to surrender to gravity, and experience whatever the falling brings – whether that is relief, pain or exhilaration.

‘I started these pictures in 2017, in response to my Dad’s death. Well, actually I’d begun it just before. I like to make work and often I don’t really know why, I like to feel quite intuitive about it, and so I’d just started making it, and then he died and it really became about grief, letting go, a lack of control and sadness. It was a physical catharsis, a way of getting through that time. While I was making it, I was also thinking a lot about the word ‘falling’ and all of the falling we do throughout life, from the mundane – falling asleep – to falling in love, falling pregnant, falling from grace, all these connotations that have falling associated to them. And while I was making this work, I fell pregnant, and so had to actually stop making it!’

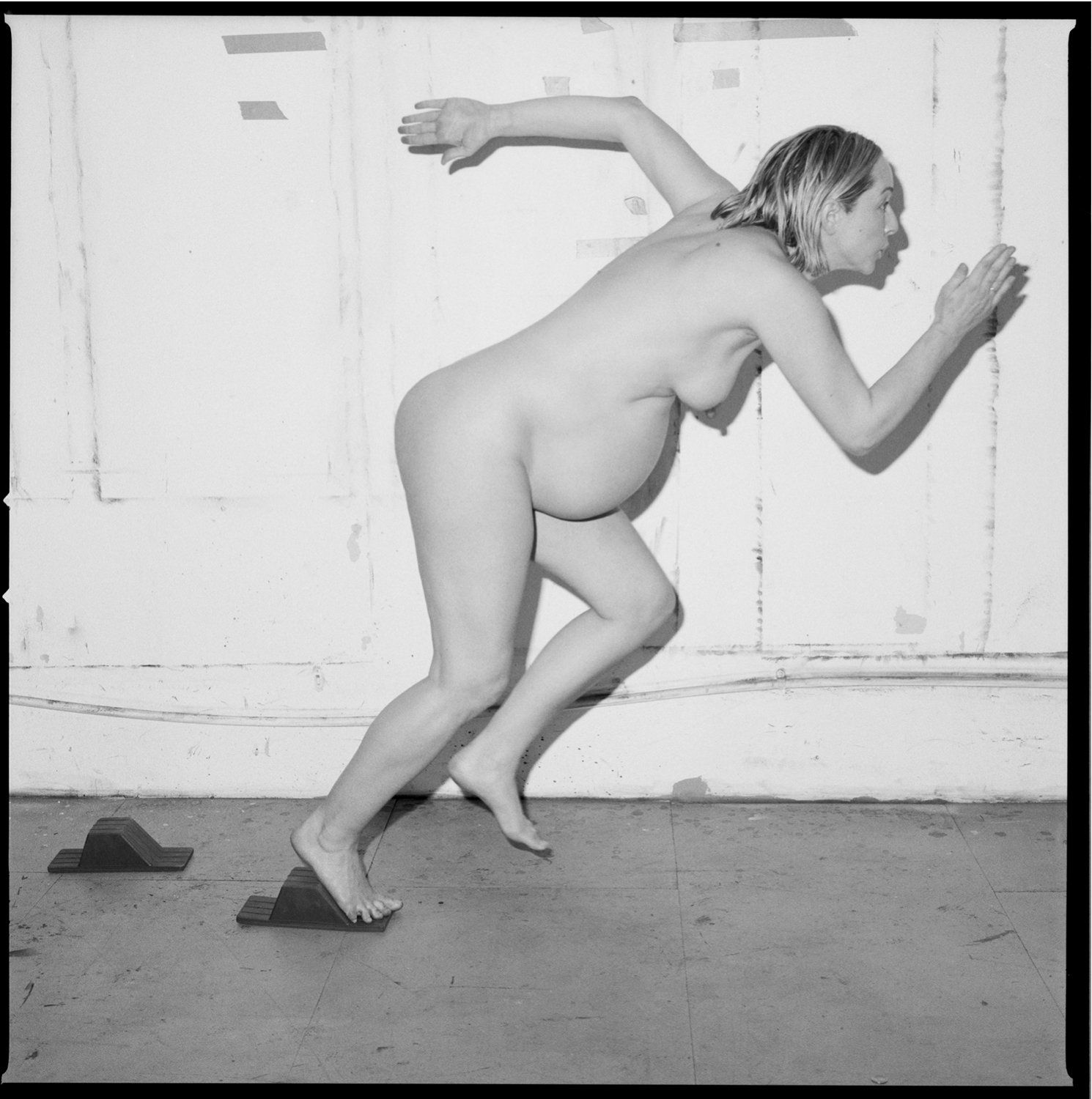

It was at this point, last year, that she made Falling Pregnant, a series of self-portraits in which Laurent, naked and heavily pregnant, is captured running off starting blocks in her studio. They show pregnancy in completely different way to the norm – instead of this moment in life being one of passivity or softness, Laurent shows it can bestow women with strength and vitality.

‘Making this work was a reaction to how powerful I felt while I was pregnant. I felt like the more active part of me hadn't been recognised in anything that I'd seen within the art world. When we’re pregnant, our hips move apart, our muscles move, it’s incredible that our body knows how to do that. How women have been depicted art historically, being soft during pregnancy or, in motherhood, not being active or powerful. I think we are both these things; we are caregivers but we can also be providers. I still feel powerful. I feel like I can achieve more than I ever have before. I feel more capable and I have much more belief in myself.’

Motherhood has inspired a deep thoughtfulness and new perspective on her relationship with her own mother, which she says is always changing. A few years ago, Laurent made a series of photographs of her mother holding her, and about these, she now reflects: ‘I was just something I wanted to do with her. In every picture, she's holding me up or picking me up. I kind of realised what a burden you can feel like as a child. Maybe a better way of putting it is, there’s an interconnectedness between mother and child. Obviously, we spend the first nine months literally carrying our children, but as time passes and your child becomes more of an individual, there is always this feeling of being connected.’

"Obviously, we spend the first nine months literally carrying our children, but as time passes and your child becomes more of an individual, there is always this feeling of being connected."

There’s a comfort that I remember from childhood, and a safety. That's the biggest thing I can thank my parents for, because I can now remodel that for my daughter. My mother thought and still thinks I'm amazing, regardless of whether I am or not, and her doing that gives me a model to be able to do that for my daughter.’

The conversation drifts to what life has been like during lockdown, and how it has illuminated connections between motherhood and our human need for empathy and connection, more generally: ‘I’ve been thinking about what motherhood means in a more symbolic sense - somebody thinking you are incredible and capable. This year, more than ever, the idea of looking out for each other, community and social structures amongst peers have meant we have all had to have broader understanding and emotional availability for our immediate and wider communities. And this is at the core of how we Mother.’

Gabby Laurent’s first book, Falling, will be published by Loose Joints in June.

?&scaleFit=poi&poi={$this.metadata.pointOfInterest.x},{$this.metadata.pointOfInterest.y},{$this.metadata.pointOfInterest.w},{$this.metadata.pointOfInterest.h}

)